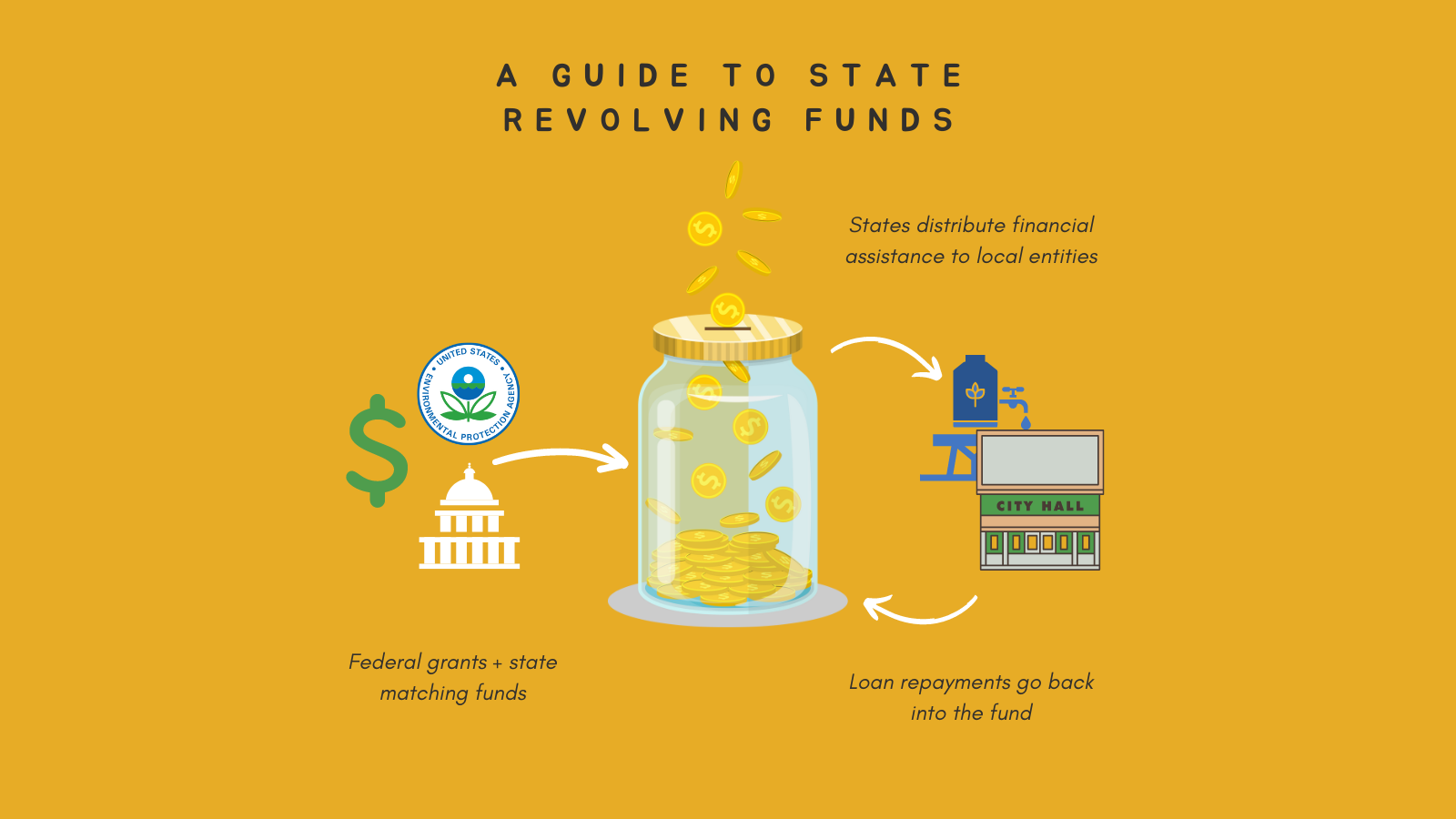

For nearly 35 years, the Environmental Protection Agency has worked with states to provide funding for water infrastructure through State Revolving Funds (SRF). There are two general SRF programs—the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) and the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF).

Once these funds reach our state, the Texas Water Development Board distributes State Revolving Funds through low-interest and forgivable loans for local governments and utility districts to plan, design and build wastewater, storm water, and drinking water infrastructure. The programs are “revolving” because as loans are paid back, the funds can then be distributed again to fund more projects across the state.

Importantly, every state has leeway to design the terms of the financing and how it wants to prioritize projects and recipients.

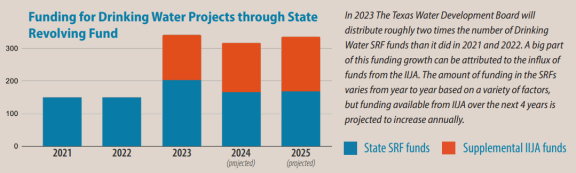

In Texas, each year about $300 million is available through the SRF programs. With the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021, it’s estimated that Texas will receive an additional $2.9 billion in funding through the SRF over five years.

The infusion of federal funding means that the state can expand the number of projects it supports in upcoming years. In 2023, the Water Development Board will distribute roughly twice the funds it did in 2022 and 2021, and through the IIJA, funding is expected to increase annually for the remaining three years.

The IIJA funds provide Texas a unique opportunity to invest in local communities. And while $2.9 billion is a lot of money, the EPA estimates that Texas will need more than $60 billion over the next 20 years to shore up our infrastructure for all residents. The additional funds provided under IIJA require that at least 49% of funds go towards disadvantaged communities.

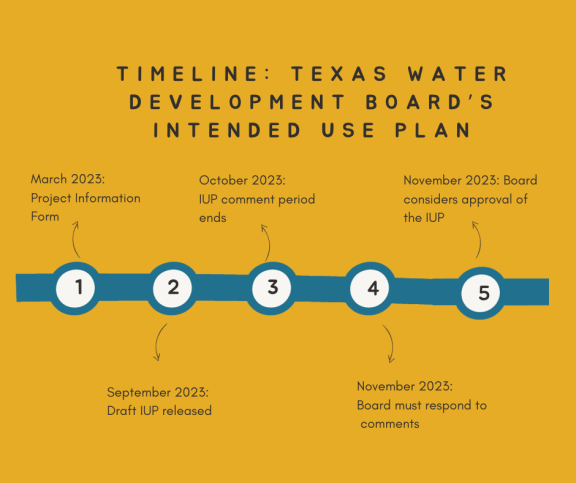

To that end, the Texas Water Development Board released its draft “Intended Use Plan” this fall for the 2024 fiscal year, which defines how the funds could be used over the next year. Our team at Texas Living Waters provided comments and received support from 10 other environmental and community organizations advocating for policy changes that would expand the reach of the funds and help Texans most in need of these investments.

TWDB currently uses annual median household income to determine whether a community qualifies as a “disadvantaged community” that can benefit from forgivable loans. Forgivable loans are often the best opportunity for many of these communities that do not have the ability to pay back loan financing. The agency also uses a “minimum household cost factor,” which aims to measure affordability for consumers who would benefit from the project.

If a community doesn’t meet both factors, they may be excluded from accessing forgivable loans.

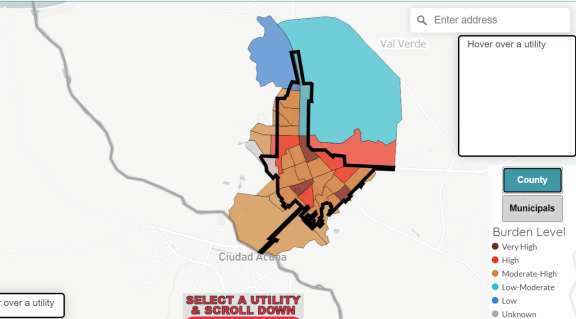

For example, the city of Del Rio has a median household income of $50,000, which meets TWDB’s threshold. According to Duke University’s Water Affordability Dashboard, a significant portion of Del Rio’s population is water burdened (meaning that they pay more than 2% of their income on water bills). But Del Rio cannot access forgiveable loans from TWDB as a disadvantaged community, because it doesn’t meet the agency’s stated threshold. If the city needs to improve its infrastructure through additional loan financing, it would likely have to pass on those costs to residents through higher water rates – increasing the water burden felt by the community. Therefore, we’ve advocated for changes to the household cost factor calculation to better identify communities that are in need of forgivable loans.

Additionally, some urban communities may not be able to qualify for forgivable loans since TWDB’s current approach does not account for more granular levels of inequality. Oftentimes, the total urban service area may have a higher median income, resulting in subsets of the area with concentrated rates of poverty or other factors losing out on funds. In other words, a neighborhood with poor infrastructure that is in the same ZIP code as wealthy neighborhoods may lose out on funds if we only rely on the area’s averages. To allow those communities to access forgivable loans, we advocated for the project service area to be used instead of the total service area of the applicant.

Next, we suggested using a more targeted approach for determining the percent forgivable loan an applicant is eligible for. With the IIJA funds, the Water Development Board must provide at least 49% of the funds as principal forgiveness to disadvantaged communities. Historically, the Board has provided either 30%, 50% or 70% principal forgiveness to eligible communities. The agency has adopted a uniform 70% principal forgiveness across the board – regardless of the community’s level of disadvantage. We know that this may not be enough for some communities—and it may be excessive for others. For certain applicants, projects cannot get built without reaching nearly 100% of principal forgiveness. That means the most under-invested communities may continue to lose out. Meanwhile, communities that can afford to pay back more of the loans will effectively withdraw dollars from the revolving fund. Therefore, we urged the TWDB to consider using a “sliding scale” that provides greater amounts of principal forgiveness for areas of greater disadvantage.

Other recommendations:

- TWDB should expand its “disadvantaged community” thresholds so that more communities in need qualify for funds.

- TWDB should incorporate a social vulnerability index in its planning process, which would identify historically marginalized communities that are already overburdened with pollution, flooding, and inadequate infrastructure.

- TWDB should adopt goals to invest in the water sector workforce, which could face worker shortages and loss of expertise in the coming decades.

A full copy of our comments is available here. We worked with an array of advocates, including Bayou City Waterkeeper, West Street Recovery, Coastal Prairie Conservancy, and others to submit these comments.

The TWDB will be considering the final adoption of the IUP during its next board meeting on November 9th. Members of the public are welcome to provide comments to the board on these issues during that meeting.

Let us know if you have any thoughts on this program and how to improve the board’s administration of these funds! You can reach us via email here.

More Resources: