This article is by Jennifer Walker, National Wildlife Federation and Vanessa Puig-Williams, Environmental Defense Fund. It originally appeared in the San Antonio Express News on Aug 7, 2023.

There’s a deep red bull’s-eye hovering over the Hill Country in the Texas drought monitor.

While drought is a part of the life cycle of Texas, we should have no illusions about the increasingly precarious state of the Hill Country’s water resources. Breakneck growth, coupled with prolonged waves of heat and aridity, mean our water and ecosystems are under immense pressure.

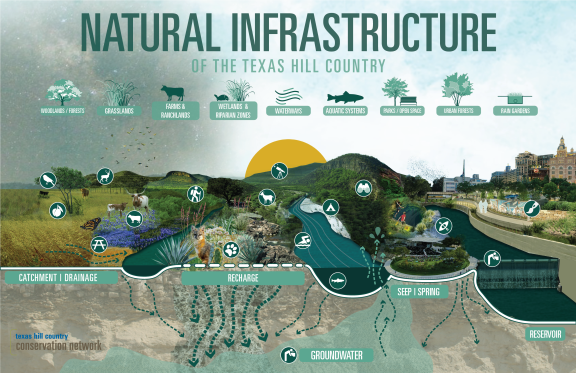

Yet it is the systems most impacted — our natural land and waterscapes — that hold the key to securing our collective water future. As a new report from the Texas Hill Country Conservation Network outlines in unprecedented detail, the Hill Country landscape is a complex set of beneficial functions that we might collectively call natural infrastructure.

Open spaces with healthy soils, trees and plant cover, and the occasional spring, seeps or creeks all act as natural infrastructure. These places are vitally important and working hard for us around the clock. They improve aquifer recharge by collecting and storing rainfall. They improve water quality via filtration — a mounting concern as phosphorus and other chemicals from human activity increasingly permeate our waterways. They retain and slow stormwater, mitigating the floods that frequently visit the region. They reduce soil temperature, which can reduce the impact of droughts. They reduce soil erosion, keeping our rivers clearer and improving our reservoirs’ capacity to hold precious drinking water.

Despite its beauty and vital hydrological function, there are growing cracks in this natural system. Climate change is leading to longer local cycles of heating and drying punctuated by less frequent but heavier flood-inducing storms. Layered on top of climate threats, the region is growing rapidly. The Hill Country’s population, 3.8 million, has grown by nearly 50 percent in the past 20 years. It is expected to grow by another 35 percent over the next 20 years. If we are to successfully harness the natural power of our landscape to mitigate water risk, we will need to address these fundamental, and growing, challenges head-on and do it soon.

There are clear pathways forward. First, we need to get a much better grip on exactly how the Hill Country’s natural systems are changing. Despite dedicating much-needed billions to water infrastructure investment and new supply build-out, the Texas Legislature ignored opportunities to update groundwater modeling and data.

The Legislature did authorize a huge potential investment in water infrastructure. Senate Bill 28 could provide Hill Country communities with some of the resources they desperately need to update and expand their aging systems. Not only could this greatly ease the burden on the region’s water resources, it’s a generational chance for communities to deliberately incorporate natural systems as key components of their water systems.

Each of us has a role to play in making sure this investment happens. On Nov. 7, Texans can put Senate Bill 28 into action by voting to approve an amendment to the Texas Constitution that will create the Texas Water Fund — the official fund that will house the approved $1 billion investment in Texas water infrastructure. This is, of course, a drop in the bucket of the projected $150 billion Texas needs for water infrastructure over the next 50 years.

As the money begins to trickle in, we would do well to remember much of the infrastructure we need to invest in is already here. It is the Hill Country itself. It is beautiful, and it works wonders for water. We need to better care for it.

Jennifer Walker is director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Texas Coast and Water Program. Vanessa Puig-Williams is director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Texas Water Program.